This paper was first presented as part of the Narratives of Climate Change Symposium, University of Newcastle, 5-6 July, 2018.

Nowhereisland is an artistic project by British artist Alex Hartley, made in 2012. It was an artwork that grew from the proposition ‘what if an Arctic island travelled south?’1 The fundamental premise of the project was to create the world’s newest nation, a borderless country with citizenship open to all.

The project began in 2004 with a Cape Farewell expedition Hartley made to the High Arctic region of Svalbard. There, his quest was to find and claim a new island.2 Calling upon the practices of nineteenth century exploration, particularly of the Arctic, Hartley kept an expedition journal. Under an entry titled SEARCH, he describes his pursuit:

I find myself monitoring the coastline, watching and checking it against the latest maps and charts: searching for the possibility of new land that might have been revealed from within a retreating glacier. In many places, the charts do not match what I am seeing. Massive glacial retreat has created a changed landscape.

Days are passing. We are over three-quarters of the way through our expedition and as yet there is no sign of the imagined island for which I am searching.3

It was important to Hartley that the island be the physical product or evidence of a changing climate. Only then could it appear as ‘new’ territory, previously unmapped and unclaimed.

Five days later, in an entry titled FIND, he writes:

We pass through the narrow strait of Helenysundet between the two islands of Spitsbergen and Barentsoya…Here there are distinct land formations that are not on the map, the charts show only the solid white of cartographic ice.

I climb the mast and from this vantage point it is clear that the land formation has sea behind it and is an island. I realise that this is it – this is new land.

A party of seven is formed and sets out toward the island in the Zodiac landing craft. The strangeness of the northern light and the lack of any human touchstone make it impossible to judge scale or distance… as we round the southern tip…I am able to step ashore on a rocky black strip of frost-shattered moraine. I am the first human to ever set foot on this island.4

Once Hartley and the crew land upon the island, they perform a set of ‘claiming’ and ‘naming’ rituals drawn from a long history of island encounter within the colonial expansion of the British empire. They anthropologically measure the miniature landscape; ‘we plot the island, and record its features. I walk the perimeter.’5 Hartley continues:

At the centre of the island, in the tradition of the claims of miners and explorers, I place a note inside a tin can (brought along for this purpose) and build a rocky cairn up around it to fix its location.6

The note stated in both English and Norwegian notice of our claim on the newly revealed land. Upon our return to the mainland our new island will be charted and I will submit it for inclusion in all subsequent maps. The land will be named and registered. The name has not yet been finalised, but I feel the most obvious Alex HartleyLand may cause some ill feelings amongst my fellow crew members.7

For Hartley, the North is an alluring landscape in both its mythological potential – artist Tania Kovats describes it as ‘a magnetism both real and in the imagination.’8 But also as a landscape under threat – it is the disappearing face of climate change.

It took six years of wrangling, between Hartley and the Norwegian Polar Institute, for his requests of control over the island to be considered. In 2010, permission was finally granted for Hartley to name the island, have it officially mapped and surveyed, and to remove parts of the island from the High Arctic for the purpose of the artistic project Nowhereisland. The original name endorsed by the Norwegian Polar Institute was Nyskjaeret; a translation from the Norwegian ny meaning ‘new’ and skjer meaning ‘skerry’ or ‘islet’.9

In 2011 Hartley and a crew of specialists in international law, environmental and political campaigning, human migration and anthropology, returned to the Arctic in order to retrieve Nyskjaeret. Under a journal entry titled DECLARATION, Hartley writes:

Exactly seven years to the day after the island’s discovery we reach international waters due north of Svalbard. In order to declare Nowhereisland a new nation we have to leave Norwegian territorial waters…Although we cross no physical line, the atmosphere is charged and our celebration is genuine and powerful as we pass out of the jurisdiction of any nation and the rocks and stones of the island become Terra Nullius.

A flare is fired and the Declaration is signed.10

On September 20th 2011 Nyskjaeret crossed international waters whereupon it became the world’s newest island nation – Nowhereisland. A kind of baptismal transformation was performed. Nyskjaeret was untethered from the specifics of location, Svalbard and the reigning Kingdom of Norway, and transformed into a non-place – the utopian artwork of Nowhereisland.

During its year-long status as the world’s newest island nation Nowhereisland journeyed over 4,000kms, tugged from the High Arctic down to the ports and harbours of the south west coast of England. Funded by the Arts Council England, Nowhereisland was commissioned for the 2012 London Cultural Olympiad. Under this context it operated as a displaced nation journeying south ‘in search of its people’, and epitomised the host-nation/visiting-nation dynamic of its Olympic setting.11

The Nowhereisland Declarationis the nation’s founding document. As Hartley described, the Declaration was read aloud, signed by all members of the crew, dated, and signalled with a flare as the island left the territorial waters of Norway.12 The declaration states:

Nowhereisland seeks to redefine what a nation can be. Nowhereisland embodies the global potential of a new borderless nation, which offers citizenship to all; a space in which all are welcome and in which all have the right to be heard. Nowhereisland’s constitution is and will be cumulative and consensual, open to all citizens and subject to change during the nation’s lifetime.13

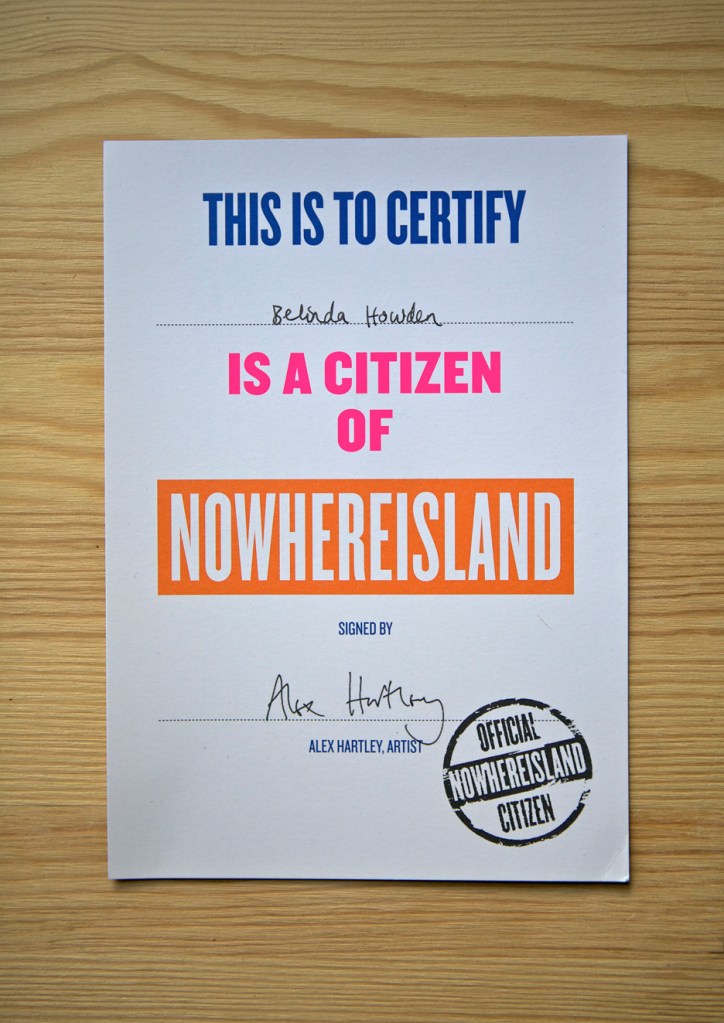

As Nowhereisland journeyed around the south west coastline of England, it was accompanied by an on-shore mobile Embassy. The Embassy was publically accessible unlike the island itself. This decision maintained the island’s position as a utopian emblem rather than as a physical site. The embassy invited the public to become citizens of Nowhereisland and was a location for contributing to the nation’s online constitution. Over the course of the project Nowhereisland accrued 23,003 citizens, drawn from 135 countries worldwide. And, it accumulated nearly 2,700 constitutional submissions created and voted upon by its citizens.

With its open citizenship, and communal democratic constitutional method, the project offers ‘Nowherians’ a moment to consider what citizenry might mean. It is a moment to consider the future of citizenry and its guiding principles. On a very mundane level, open citizenship provides basic access to the content of the project. Nowhereisland is inert and unfinished if not enlivened by its citizens. Poetically speaking though, open citizenship offers symbolic reprieve from the large-scale bureaucratic processing of human lives. Although the project is bound, in many ways, to the processes and traditions of nation-building, its open constitution rather ironically contradicts the real-world political rhetoric surrounding nationalism and nationhood. It offers a symbolic antidote to the current heightened state of border security and border control.

Nowhereisland’s open citizenship is self-described as a type of ‘insurgent citizenry’, reminiscent of the Occupy movement.14 It also reflects a 21st century method of organisation. In stark contrast to almost all other recognized nation-states, no forms of assessment or suitability are required (an internet connection being the only exception). The international reach and rhizomatic model of citizenship makes being Nowherianakin to being a global citizen.15

Nowhereisland’s constitution proves to be an education in desire. Of 2,678 propositions, ordered most popular to least, the constitution convalesces around six major subjects: citizenship, nationhood, migration, art, environment and behavior. At 427 up-votes, the number one constitutional rule is: ‘Every Nowherian has the right to be silent’.16 Closely followed by: ‘Every Nowherian has the right to be heard’.17

Of course, not all submissions are so serious. There is plenty of folly: ‘There should be a free and constant supply of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream for all citizens’; ‘Weekends will be three days long’; and, ‘The only deity acceptable to worship will be Jennifer Garner’.18

But, Nowhereisland does manage to touch upon burgeoning questions of the twenty-first century. At least eight propositions share the sentiment that no politicians or political parties are allowed on the island. The 7th most popular submission is strangely prescient: ‘wherever we may consider building a wall, fence or barrier we should instead place a table.’19 Nowherians have determined that war is forbidden on their island, guns are unanimously banned. The notion of universal free healthcare is resounding whereas the subject of education raises more divergent views. The trappings of nationhood also prove tricky. When one citizen proposes ‘We shall worship no flag’, the next states that not only should Nowhereisland have a flag but that ‘flag should be designed by Rolf Harris.’20

In her book The Concept of Utopia, British sociologist Ruth Levitas places desire at the heart of any utopian strategy. She suggests that utopia is an education of desire; utopia is not just a question of ‘what may I hope?’, but a question of ‘what may I dream?’.21 She writes:

Utopia expresses and explores what is desired; under certain conditions it also contains the hope that these desires may be met in reality, rather than merely in fantasy. The essential element in utopia is not hope, but desire – the desire for a better way of being.22

Nowhereisland echoes this sentiment. On the project website it states:

Nowhereisland began in a place far from the noise of the urban centres of the Western world. Far (it would seem) from the passport controls and security checks of our journeys across national boundaries. Far from the riots and protests of our streets. Far from the ringing of our phones, the buzzing of our cash points, the tapping of our keyboards… [It is] not simply an imagined place – nowhere or ‘utopia’ – but a tool for imagining our world ‘as if things were different’ and as an urgent call to action.23

The way in which Nowhereisland came to an end is also significant. Once constitutional submissions had closed and citizens had long-finished voting, the excavated rock of Nsykjaeret was dismantled and disseminated to each and every Nowherian. Dispersed across the globe, a small chunk of the Arctic island now sits on the mantelpiece or hangs on the walls of its 23,003 citizens.

This act transforms Nyskjareet and the project of Nowhereisland into a wholly utopian realm. It is no longer a physical place we can visit. This chunk of rock is now a souvenir. British geographer and poet Tim Cresswell, who was also a crew member of the 2011 expedition, describes Nowhereisland as performing a kind of ‘spatial magic not unlike voodoo’.24 Nowhereisland not only looks like Nyskjaeret, it is scaled down replication of the original Arctic island. But, it is also ‘made from the very stuff of Nyskjaeret.’25 It is both a product of climate change and a figure for addressing its problems.

We can question the undertow of Hartley’s romanticism towards colonial practices, language and posturing. We can also question the lasting effect of an artwork, like Nowhereisland, as a lightning rod for real social or political change. But, if we consider the sheer scale of the project– the number of team members and those aboard the expeditions; the amount of money the project attracted; the number of corporate, commercial and private partnerships; the time involved to not only produce the work but the duration of the artwork itself – Nowhereisland is too involved and too purposeful, with too many contributors, to be anything but a deeply politicised artwork. As ‘a conceptual nation involving thousands of people across the world shaping that nation’s values and principles online,’ Nowhereisland operates as a tool for dreaming.26 Its open constitution jostles with real concerns about new or alternative social and political structures. Amongst its whimsy, it does propose a citizen-invented shape of a nation-state in the twenty-first century.

In my closing thoughts, I would like to read you a letter written to the citizens of Nowhereisland. Simon Arnholt, a British independent policy advisor, was invited to reflect on Nowhereisland as part of the project’s Resident Thinkers program. As part of the letter, he writes:

One of the reasons why we have always found it so difficult to think constructively about the shared, borderless, supranational challenges that define our age is because we come from countries, we live in countries, we travel between countries, we define our loyalties by countries…at this point in our history, a place that’s truly nowhere has more value and interest than a place that, just like everywhere else, is somewhere. There could be no better vantage-point to take a fresh, clear, cool, hard non-country look at the world and see what we can do to solve these non-country problems.27

- Claire Doherty et al., “Nowhereisland in Review,” (Situations, December 2012). Pg5

- Alex Hartley, “2004 Expedition Blog – Day 11,” Cape Farewell, http://www.capefarewell.com/2004/2004blog/day-11.html

- Hartley, Nowhereisland. Pg41

- Ibid.

- Hartley, Nowhereisland. Pg71

- Hartley, Nowhereisland. Pg71

- Hartley, “2004 Expedition Blog – Day 11”. Accessed 4 April 2016

- Tania Kovats, “Nowhere”, Nowhereisland. Pg29

- Letter from the Norwegian Polar Institute. Dated 2 June 2006. Alex Hartley, Nowhereisland (London: Victoria Miro, 2015). Pg79

- Hartley, Nowhereisland. Pg95

- Rachel Cooke, “Alex Hartley: The World Is Still Big – Review,” The Guardian Sunday 27 November 2011.

- Nowhereisland. Pg95

- Hartley, A. et al. “The Declaration”, Citizenship, “Nowhereisland”. Accessed 4 April 2016

- “Citizenship”, Embassy, ibid. Accessed 4 April 2016

- Ibid.

- Nowhereisland, “The Nowhereisland Constitution,” (Situations, 2012). Accessed 4 April 2016

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Pg123 and 220

- Ibid. Pg221

- “Intro”, Embassy. “Nowhereisland”. Accessed 4 April 2016

- Cresswell, “The mobilities of Svalbard”. Pg33

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Simon Arnholt, ‘Letters to an Island’, Nowhereisland (London: Victoria Miro, 2015). Pg103